Ghost in the Machine: Marc Gysemans & the Programming of Antwerp Fashion

A look at how one clothing manufacturer helped fuel Antwerp’s meteoric rise

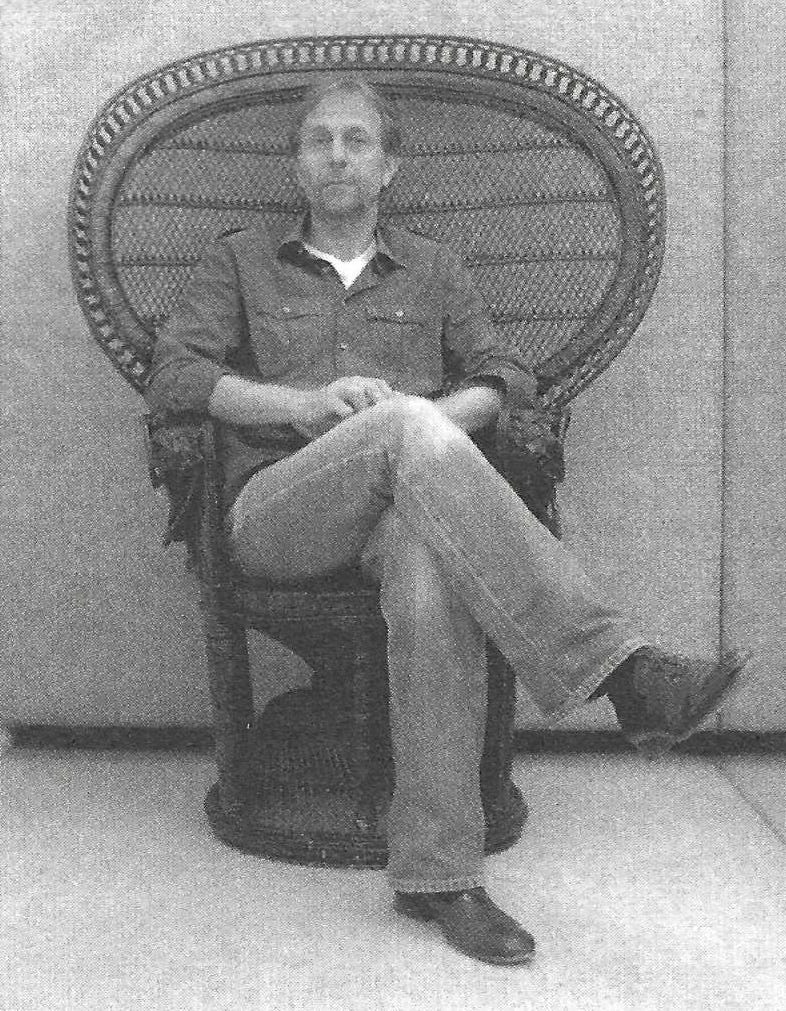

Of the many names that come to mind in Belgian fashion, Marc Gysemans may not be the first. A clothing manufacturer by trade, Gysemans Clothing Industry was the manufacturing and (and sometimes financial) powerhouse behind many of the famous Antwerp designers: Raf Simons, Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, and Veronique Branquinho, to name a few.

Marc Gysemans started in the fashion business in 1982 as head of production at a t-shirt manufacturing company. After a brief stint as temporary head of the company, he would go on to form his own eponymous enterprise in August 1986, taking space in the Manhattan Building in Leuven, Belgium (about an hour’s drive from Antwerp). Gysemans would begin operations in a 180 m² room on the first floor, operating here and quietly expanding until an eventual move to a permanent home in Rotselaar nine years later.1

Simultaneously, the Antwerp Six had just begun to emerge, as 1986 was the same year that the group headed to a London Trade show, making their first big impression on the fashion scene.2 Gysemans, still just a fledgling operation at the time, soon became the node for the Antwerp Six’s production, mostly due to similar circumstances–established European manufacturers at the time found the Antwerp Six too risky and avant-garde; likewise, Gysemans was a still nascent business, with few established clients. Gysemans, recalling the birth of this relationship, cited: ‘I was never interested in large quantities…it was a natural progress that developed over time. You start to become interested in your clients, you become familiar with their world.’3 This symbiotic relationship would soon become the burgeoning engine of Antwerp’s fashion revolution.

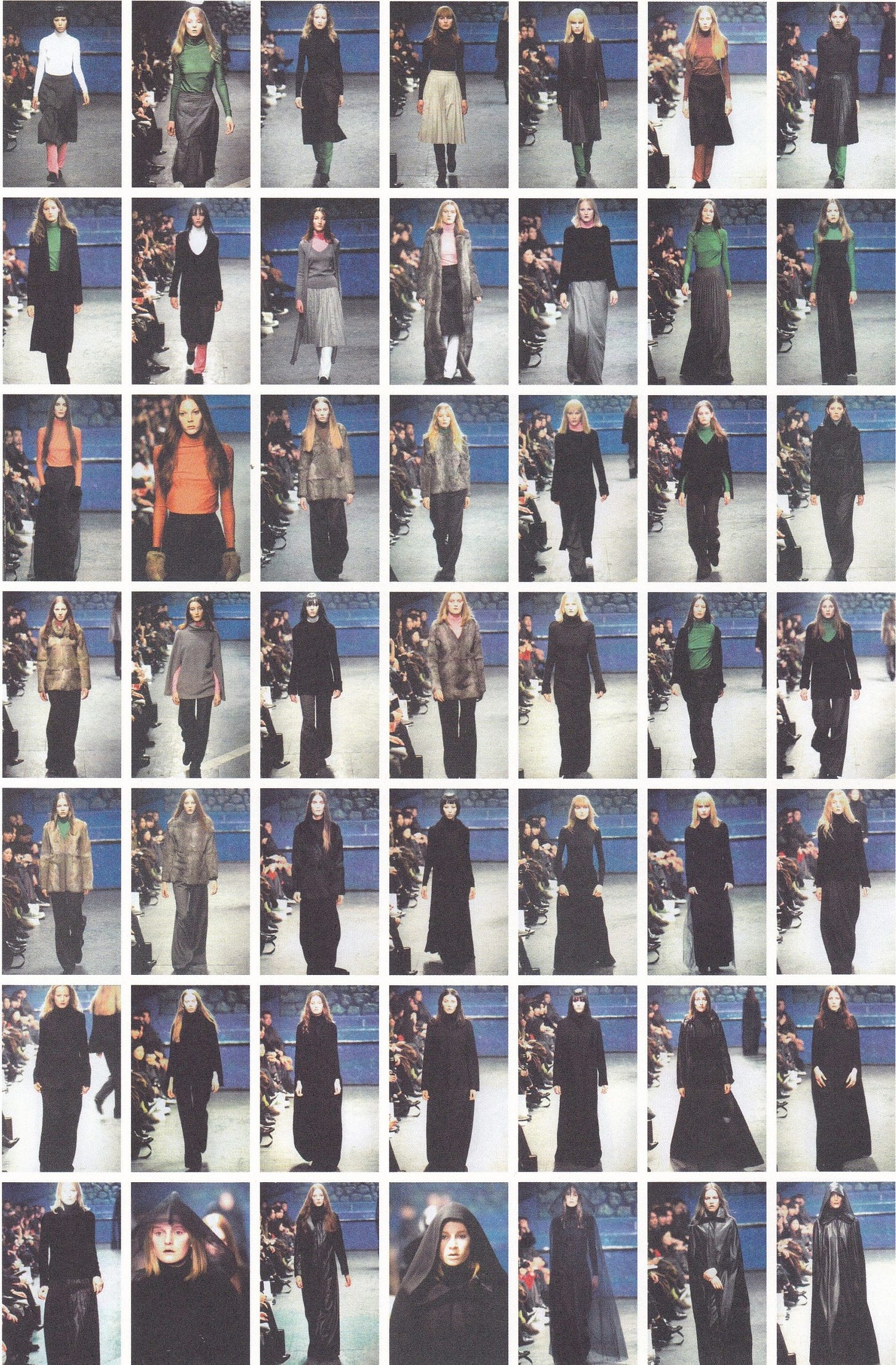

Aside from manufacturing, Gysemans would also move into financial backings and arrangements with young Belgian designers. In late 1997, Gysemans offered to finance and produce Veronique Branquinho’s debut Paris Fashion Week collection (Fall-Winter 1998), a rare move for a manufacturer at the time. This financial backing allowed her to open a showroom in La Bastille and also to produce an accompanying publication; “Without him, I wouldn’t have been able to do this,” she recalled at the time.4 Branquinho and Gysemans would soon form a jointly owned venture, entitled NV James, with Gysemans taking a 50 percent stake in ownership.

Gysemans told WWD at the time: “It’s all about teamwork…I try to be like the Italians who have been backing designers for 20 years, but this is new for Belgium.”5 Looking back on their partnership in 2005, Gysemans told Dutch business magazine Trends:

‘In the beginning, I was the main investor. I produced the samples, paid for the showroom in Paris and financed the production. The collection immediately went very well. I am still a silent partner in NV James (alongside Veronique Branquinho and her business right-hand man Raïssa Verhaeghe) and part of the collection is produced in my studios.”6

In this way, Gysemans became a patron and creative force, shaping Antwerp fashion by selecting young designers to financially and operationally back. Gysemans would often attend shows with Linda Loppa, the famed director of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Art in Antwerp, in order to scope out young and up and coming designers he could promote, similar to his approach with Branquinho.

While the Branquinho partnership exemplified Gysemans’ role as a patron, his work with Raf Simons showed a knack for rescuing designers from logistical and financial crises. In March of 2000, soon after the Branquinho deal, Raf Simons would abruptly quit the fashion world, temporarily shutting down his label. Citing an overwhelming pace and a growing frustration with the business elements of fashion, (along with an opportunity to take a position as head of the Vienna University of Applied Arts’ Fashion Department), Raf would depart the fashion world near top of his popularity.7 A few months later, a deal was struck with Gysemans to resume production for his Autumn/Winter 2001-2002 season, 'Riot Riot Riot’.

Speaking again in Trends, Gysemans described the renewed deal with Raf Simons:

“I produced for him for years, but at the same time my team also did the sales and distribution for him. He received a fee on the sales. That has changed now: I continue to produce for him, but the sales are done via a distribution house in Italy and Japan. I am handing over the commercial side in this case, perhaps because I was a bit too close to it.”8

The early oughts also held promising partnerships with even younger Belgian designers such as Tim Van Steenbergen and Kris Van Assche, despite a gloomy outlook for Belgian fashion overall. Gysemans would entered into financial arrangements with both designers similar to the one with Branquinho.

Gysemans would eventually shift manufacturing from Belgium to Romania around 2006, citing lower operational costs and efficiency.9 Development and distribution would still remain centered at the company’s original headquarters in Rotselaar, Belgium. This fell in line with a worrying yet growing trend of the dissolution of domestic manufacturing in Belgium, with Antwerp designers publicly lamenting the state of affairs at home. Dries Van Noten would tell WWD in 2003:

“We needed to get better prices”, said Van Noten. “People no longer want to work in factories in Belgium. It’s a pity. Young designers got a lot of help from the local manufacturers.”10

Scale was the most commonly referenced fault point, along with an overly strong euro and even the SARS epidemic. Yet still, the optimism of Belgian domestic manufacturing, specifically Gysemans, couldn’t seem to be replicated internationally, with a penchant for betting on hard edged experimentation seemingly still only found at home in Belgium.

Perhaps Walter Van Beirendonck summarized the situation best:

“There has never been one Belgian style, ”Van Beirendonck said. “But the designers here share a similar approach to fashion. We’ve been more intellectual and experimental. But that fashion moment is now over. Fashion’s about celebrity and making women look like sex objects now. People are beginning to wonder if Belgian fashion is now out of fashion.”11

Nearly 20 years of hindsight might now show this mid-oughts period as the fulcrum point in which the hard edged, optimistic furor of Antwerp fashion cooled off, coinciding with increasingly difficult domestic economic conditions and the inevitably ensuing outsourcing. Yet Gysemans’ legacy endures, not just in the collections he produced, but in the risks he embraced and strategic systems he engineered behind the scenes. Without his alchemical mix of manufacturing prowess, vision, and capital, Antwerp fashion’s furious wave might never have crashed on the world in the way we know it today.

___, Antwerp’s Rising Star, Women’s Wear Daily, 6 January 1998

___, Paris Report, Women’s Wear Daily, 5 January 2000

Trends Beleggen, Wie is wie in de zakelijke coulissen achter de Belgische mode?, 3 March 2005

Simons, Raf, de Potter, Peter (eds.), Raf Simons Redux, Fondazione Pitti / Charta, 2005

Trends Beleggen, Wie is wie in de zakelijke coulissen achter de Belgische mode?, 3 March 2005

___, ‘The Belgian Blues: Designers Wonder if the Avant-Garde is Over’, Women’s Wear Daily, 9 October 2003

___, ‘The Belgian Blues: Designers Wonder if the Avant-Garde is Over’, Women’s Wear Daily, 9 October 2003